Combining neoadjuvant and adjuvant immunotherapy breathes more life into the growing body of lung cancer treatment paradigms

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, with an estimated 2.2 million new cases diagnosed and 1.8 million deaths worldwide in 2020 (1). The 5-year survival rates of lung cancer in the United States and China range from 20–40%, and most patients are diagnosed with locally advanced or metastatic disease, as the disease is often asymptomatic in the early stages (2,3). Timely discoveries and advances, particularly in the treatment of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), have led to more options in locally advanced and metastatic stages with the prospect of better survivals than those reported historically. The development of immune checkpoint inhibitors represents one of the most promising breakthroughs thus far in the treatment of NSCLC. Trials such as KEYNOTE-671 (4) continue to inform clinicians of evolving treatment paradigms for patients with locally advanced NSCLC that may be particularly effective.

Since 2016, immunotherapy drugs targeting the programmed cell death receptors on T-cells [programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1)] have been approved as an option in the treatment of NSCLC (5). By binding PD1 on T-cells, tumors expressing PD-L1 evade immune attack. The blockade of these receptors, and thus the elimination of an evasive mechanism, was shown to be an effective treatment of NSCLC in previous trials (6-13). Pembrolizumab was approved as a first-line, single-agent treatment for NSCLC in the metastatic setting after the KEYNOTE-024 trial demonstrated significantly better disease-free survival and overall survival at 6 months in patients treated with pembrolizumab compared to patients treated with chemotherapy (6). Previous trials demonstrated a clear benefit of pembrolizumab in both locally advanced, resectable disease (7,8), as well as metastatic NSCLC (6,11,13,14). Current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend pembrolizumab, in combination with chemotherapy, as the first-line treatment of choice for patients with advanced or metastatic NSCLC, and can be continued for up to 24 months as maintenance therapy (15).

Until recently, the current literature heavily focused on the employment of immunotherapy in the treatment of advanced or metastatic NSCLC, rather than in early, resectable stages of disease. In their landmark paper, Wakelee et al. report the results of a phase III, international, double-blinded, randomized, controlled KEYNOTE-671 trial for resectable stage II, IIIA, or IIIB NSCLC, in which 797 patients were randomly assigned to receive either neoadjuvant pembrolizumab or placebo, in addition to cisplatin-based chemotherapy for 4 cycles, followed by surgery and adjuvant pembrolizumab or placebo (4). At a median follow-up of 25.2 months, a significant difference in event-free survival (EFS) was observed between the pembrolizumab and the placebo group [62.4% vs. 40.6%, hazard ratio for progression, recurrence, or death—0.58; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.46–0.72; P<0.001]. The EFS benefit with pembrolizumab generally was consistent across all the subgroups analyzed (4). Interestingly, the benefit of pembrolizumab was similar among patients with squamous and non-squamous histology (4), a finding that has varied across prior studies (6-8,10,12). While the majority of these studies demonstrate that the benefits of immunotherapy are greater for patients with nonsquamous histology, as evidenced by smaller hazard ratios (7,8,12), in all cases the CIs overlapped and thus the true differential benefit has yet to be elucidated.

Whether defined as a threshold value or evaluated along a continuum, increasing PD-L1 tumor proportion score appeared to be inversely proportional to the hazard ratio for an adverse event or death. There was little difference between the estimated 24-month overall survival—80.9% (95% CI: 76.2–84.7%) in the pembrolizumab group and 77.6% (95% CI: 72.5–81.9%) in the placebo group (P=0.02). However, as evidenced by their overall survival curves, there is a continued separation after the 24-month mark in favor of the pembrolizumab treatment group (4). Based on this trajectory, the overall survival benefit of immunotherapy may be seen at longer follow-up, as seen in the 5-year follow-up analyses of prior immunotherapy trials (16,17).

A major pathological response, defined as ≤10% viable tumor cells in resected primary tumor and lymph nodes, occurred in three times as many patients receiving pembrolizumab (30.2%; 95% CI: 25.7–35.0%) compared to placebo (11.0%; 95% CI: 8.1–14.5%, P<0.0001). Similarly, a pathological complete response occurred in 18.1% (95% CI: 14.5–22.3%) and 4.0% (95% CI: 2.3–6.4%), respectively (P<0.0001). On further exploratory analysis, the EFS benefit seen in the pembrolizumab group was maintained regardless of major pathological response, suggesting that adjuvant immunotherapy could play a greater role in attenuating disease progression, recurrence, and survival in the postoperative setting and perhaps even in a maintenance paradigm (4). To some clinicians, this finding represents the most important observation noted in this trial. The phase III KEYNOTE-091 and IMpower010 trials support this claim, in which patients who received adjuvant immunotherapy had improved disease free survival (7,12). The question of whether pembrolizumab or other immunotherapies can be given as adjuvant monotherapy, or if the cytotoxic effects of chemotherapy continue to augment the effect of immunotherapy, remains to be seen.

Interestingly, the R0 resection rate in the KEYNOTE-671 trial was 75.5% in the immunotherapy group compared to 66.9% in placebo (data found in Supplementary Appendix of the study by Wakelee et al.) (4). Previous studies have suggested that surgical resection may be more difficult in patients who receive immunotherapy compared to those who did not receive neoadjuvant therapy or received chemotherapy alone (18,19). These assertions, however, are subjective assessments by individual surgeons and, in actuality, the surgical complexity has been difficult to quantify. Additionally, the greater R0 resection rate may be confounded by the higher pathological response rate seen among patients receiving immunotherapy.

The results of this study pave the pathway for future investigations. The KEYNOTE-671 trial did not report the impact of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and other biomarkers in their entirety. As treatment strategies will be refined based upon the outcomes associated with these elements, further forthcoming details in this area will be eagerly anticipated from trials such as the KEYNOTE-671 and others. Among many potential applications of ctDNA and in the context of a trial such as the KEYNOTE-671, identifying a particular threshold or a differential from the neoadjuvant phase to the postoperative state, respectively, could provide guidance as to who may benefit from adjuvant therapy. Identifying a specific value, especially for those who had a major pathologic response or pathologic complete response, may prove to be particularly impactful. Conversely, patients who do not meet such thresholds or differentials could provide guidance as to who may benefit from either conventional or alternative forms of therapy. A trial of such high quality as the KEYNOTE-671 lends itself to asking these types of questions, and as more details pertaining to the biomarker correlates are analyzed, increasingly finetuned recommendations will ensue.

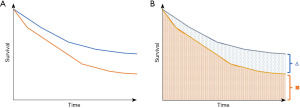

As the authors mentioned, the relative contribution of neoadjuvant and adjuvant components of immunotherapy were not addressed in this trial (4), and, a larger trial with four arms would be necessary in order to assess the relative contributions of perioperative therapy in this setting. This result draws an interesting parallel. The lung adjuvant cisplatin evaluation meta-analysis frequently has been used to justify the use of traditional adjuvant therapy in patients with stage IB–II disease owing to a 5–6% improvement in overall survival (20), and up to 8.9% with the cisplatin-vinorelbine chemotherapy regimen specifically (21). On face value the conclusions are valid. However, one must realize that in order to achieve the 5–6% survival advantage, all-comers must be treated and therefore the majority of patients who have stage II disease may not derive this exact survival benefit. In a similar manner, with the lack of other treatment arms and the absence of additional biomarker data, there may be a need to treat all patients who enter this paradigm of neoadjuvant immunotherapy followed by adjuvant immunotherapy, in order to achieve and observe a differential benefit among a fraction of these all-comers. The theoretical differential survival benefits are illustrated in Figure 1. Since other studies that have not employed adjuvant monotherapy may have issues with this approach, further investigation and reporting of more nuanced data will be required to delineate who will benefit from the use of adjuvant immunotherapy. It is understood that the KEYNOTE-671 trial did not treat all of their patients with adjuvant pembrolizumab, however, knowing who to include in this paradigm will afford us more knowledge to guide care. Since the decision to pursue a specific treatment model is often made prior to rendering any therapy, especially in a landscape where different treatment regimens are emerging, having this granular information will be of critical importance.

Taken together, the results of this trial further support the use of immunotherapy in both the neoadjuvant and adjuvant setting inclusive of surgery for NSCLC. In particular, the study design of the KEYNOTE-671 is one of its many strengths with a relatively large population examined and closely matched between groups (4). Pembrolizumab-carboplatin-pemetrexed remains the first-line standard therapy for patients with NSCLC lacking targetable mutations. The findings in this trial demonstrate that the addition of pembrolizumab in the neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings lead to significant improvements in EFS, major pathological response, and pathological complete response, with a positive overall survival trajectory at the two-year mark. While longer-term readouts from the KEYNOTE-671 trial as well as from other similar trials will shed greater light on the role of neoadjuvant and adjuvant immunotherapy in locally advanced and resectable NSCLCs, the current revelations add to a body of data that, at best, previously remained in a state of equipoise.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by Jeffrey P. Smith Endowed Chair Fund (to A.W.K.).

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, AME Clinical Trials Review. The article has undergone external peer review.

Peer Review File: Available at https://actr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/actr-23-23/prf

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://actr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/actr-23-23/coif). A.W.K. receives support from Jeffrey P. Smith Endowed Chair Fund and has financial interests with Roche-Genentech steering committee. The other author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021;71:209-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ganti AK, Klein AB, Cotarla I, et al. Update of Incidence, Prevalence, Survival, and Initial Treatment in Patients With Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in the US. JAMA Oncol 2021;7:1824-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- He S, Li H, Cao M, et al. Survival of 7,311 lung cancer patients by pathological stage and histological classification: a multicenter hospital-based study in China. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2022;11:1591-605. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wakelee H, Liberman M, Kato T, et al. Perioperative Pembrolizumab for Early-Stage Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2023;389:491-503. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Squamous-Cell Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;373:123-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1823-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Felip E, Altorki N, Zhou C, et al. Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (Impower010): a andomized, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2021;398:1344-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, et al. Neoadjuvant Nivolumab plus Chemotherapy in Resectable Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2022;386:1973-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2018-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a andomized controlled trial. Lancet 2016;387:1540-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mok TSK, Wu YL, Kudaba I, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): a andomized, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019;393:1819-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O’Brien M, Paz-Ares L, Marreaud S, et al. Pembrolizumab versus placebo as adjuvant therapy for completely resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091): an interim analysis of a andomized, triple-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2022;23:1274-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paz-Ares L, Luft A, Vicente D, et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy for Squamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2040-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2078-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®). Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Version 3.2023. 2023.

- Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Five-Year Outcomes With Pembrolizumab Versus Chemotherapy for Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score ≥ 50. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:2339-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Novello S, Kowalski DM, Luft A, et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Chemotherapy in Squamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: 5-Year Update of the Phase III KEYNOTE-407 Study. J Clin Oncol 2023;41:1999-2006. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sepesi B, Zhou N, William WN Jr, et al. Surgical outcomes after neoadjuvant nivolumab or nivolumab with ipilimumab in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2022;164:1327-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stiles BM, Sepesi B, Broderick SR, et al. Perioperative considerations for neoadjuvant immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2020;160:1376-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pignon JP, Tribodet H, Scagliotti GV, et al. Lung adjuvant cisplatin evaluation: a pooled analysis by the LACE Collaborative Group. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3552-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Douillard JY, Tribodet H, Aubert D, et al. Adjuvant cisplatin and vinorelbine for completely resected non-small cell lung cancer: subgroup analysis of the Lung Adjuvant Cisplatin Evaluation. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:220-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Theeuwen HA, Kim AW. Combining neoadjuvant and adjuvant immunotherapy breathes more life into the growing body of lung cancer treatment paradigms. AME Clin Trials Rev 2024;2:10.